Game Engine Comparison

GMS2, Unity, Unreal, Godot

It’s another CS Club meeting, and this week we’re covering one of the most fun topics in computer science—game dev!

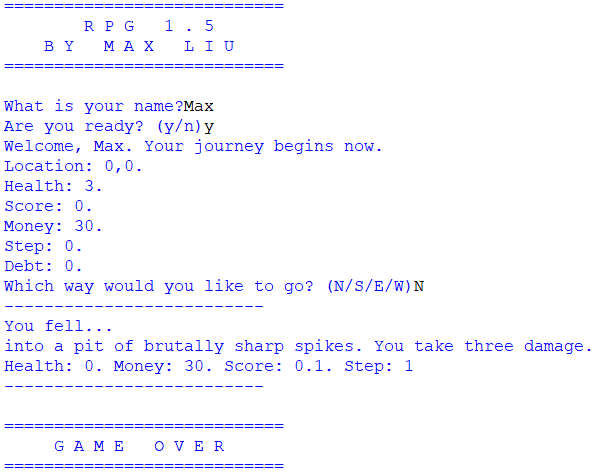

Like many people, I first became interested in programming through video games. Soon I wanted to make my own! But how? It seems like such a challenge to go from lines of code to a fully-fledged game. So probably your first game looked something like this:

My first game, a text-based RPG in Python.

And if you’re ambitious, or attended our meetings last year, you got your first taste of game dev through PyGame or some other game library:

But now you want to make an actual game and you don’t know what to do! Someone tells you to “just use a game engine and it’ll be easy”. The question now is, which engine? This article is meant to provide a guide and explanation of several major game engines. If you’re familiar with game development, you’ve already read pages and pages of comparisons between Unity and Unreal Engine, or heated arguments over what the engines can or can’t do.

The truth is that you can make great games in all of the engines we’re going to go over. But different engines are good at different things. You could hammer in a nail with a baseball bat if you wanted to, but it’d take more time and be way messier. Considering that this is the first choice you’ll make in game dev, it’s one worthy of attention. And depending on what your needs and goals are, choosing the right engine could make or break your game. So let’s compare!

GameMaker Studio 2

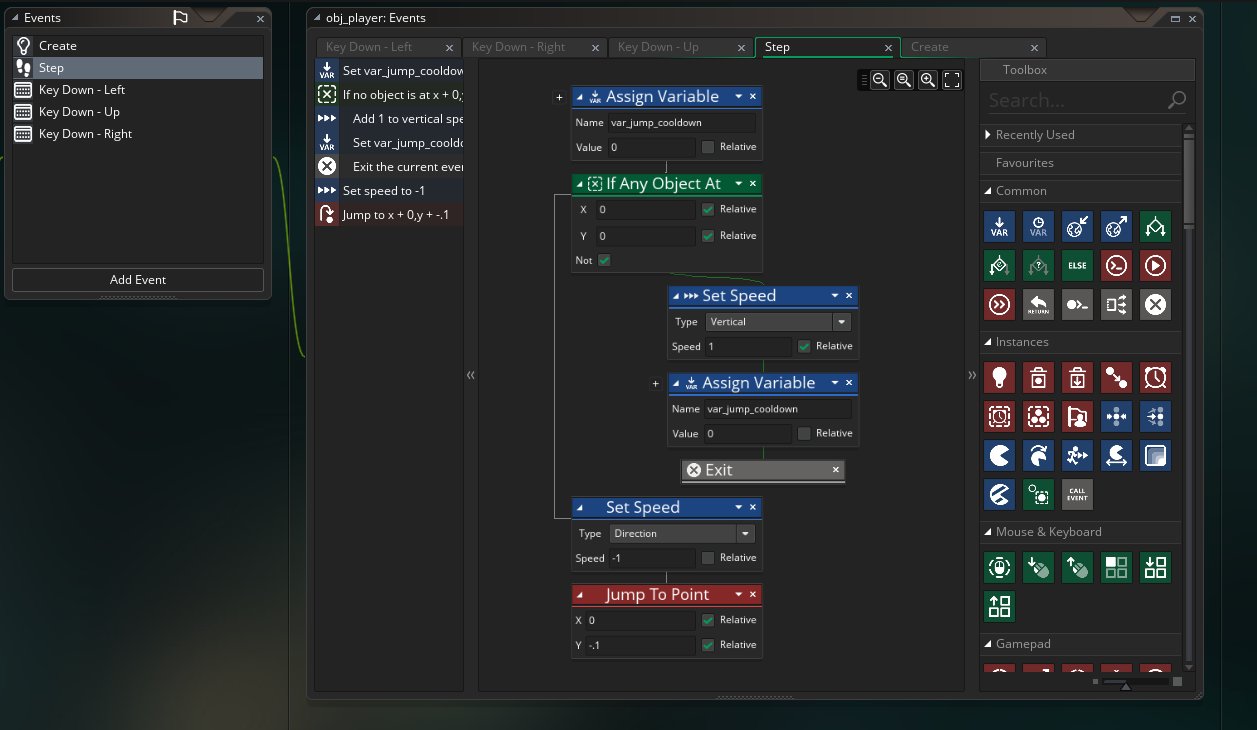

GameMaker Studio 2 is a great way to make a game with minimal code! You can drag a few objects around and end up with a fully functional game. But is it still a good beginner-friendly option, and do its limitations hold it back too much to be usable?

For Beginners?

GameMaker began as a janky and buggy piece of software, dedicated mostly for animations. Because of this, it has an old reputation of being only for beginners, or being only useful for simple games. But games like Risk of Rain and Undertale/Deltarune proved that highly successful indie games could be made with the engine.

GameMaker’s scripting language is GML, a high-level, dynamically typed language. It’s similar to JavaScript and is convenient and quick to use. However, it often produces unprincipled code—for example, draw_rectangle, draw_rectangle_colour, draw_roundrect, and draw_roundrect_colour are four different functions! There are also drag-and-drop functions available, turning the language into something like Scratch or Snap.

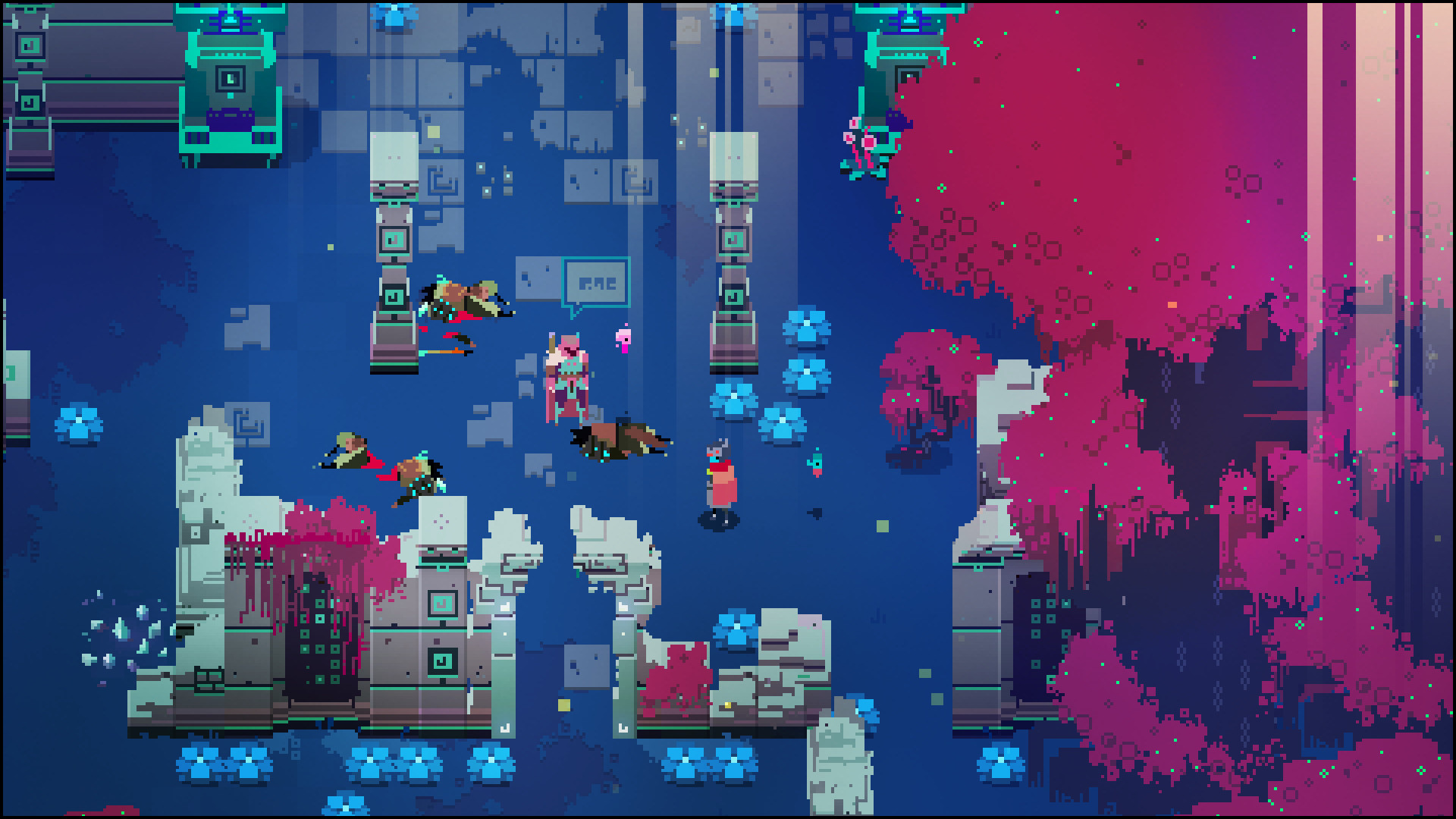

It’s still a great engine for beginners, but seems to be on the downtrend. Games can’t even be exported for desktop without a monthly subscription, and free 2D engines like Godot are becoming more and more popular. The peak of GMS2 may have been 2016-2017, with beautiful games like Hyper Light Drifter coming out:

Is It Capable?

Let’s get it out of the way—you shouldn’t use GameMaker to make a 3D game. GameMaker excels at 2D and especially pixel-based games, but has poor performance and forces you to use GML and drag-and-drop. Chances are, your large GameMaker project will end up being a pile of flaming garbage at the end because of the weak scripting and massive limitations of drag-and-drop.

It’s fun, though.

Unity

Unity is the most popular engine for indie game developers right now. There are a wealth of resources on Unity, and it has a great asset store, which lets you quickly jump into making all kinds of games, 2D and 3D.

It uses C# for scripting, which is a happy medium between C++, which can be difficult to write and manage, and visual scripting, which can end up confusing in large projects. Unity is free to export on many platforms, including mobile, desktop, and web. You will get the classic Made with Unity splash screen, though.

Jack-Of-All-Trades?

Unity is currently the most versatile engine. It’s been used to make artistic and dynamic 2D games, like Cuphead and Hollow Knight. But it can also pump out beautiful and cutting-edge 3D games like Subnautica: Below Zero and Outer Wilds.

A screenshot from the 2018 game Escape From Tarkov.

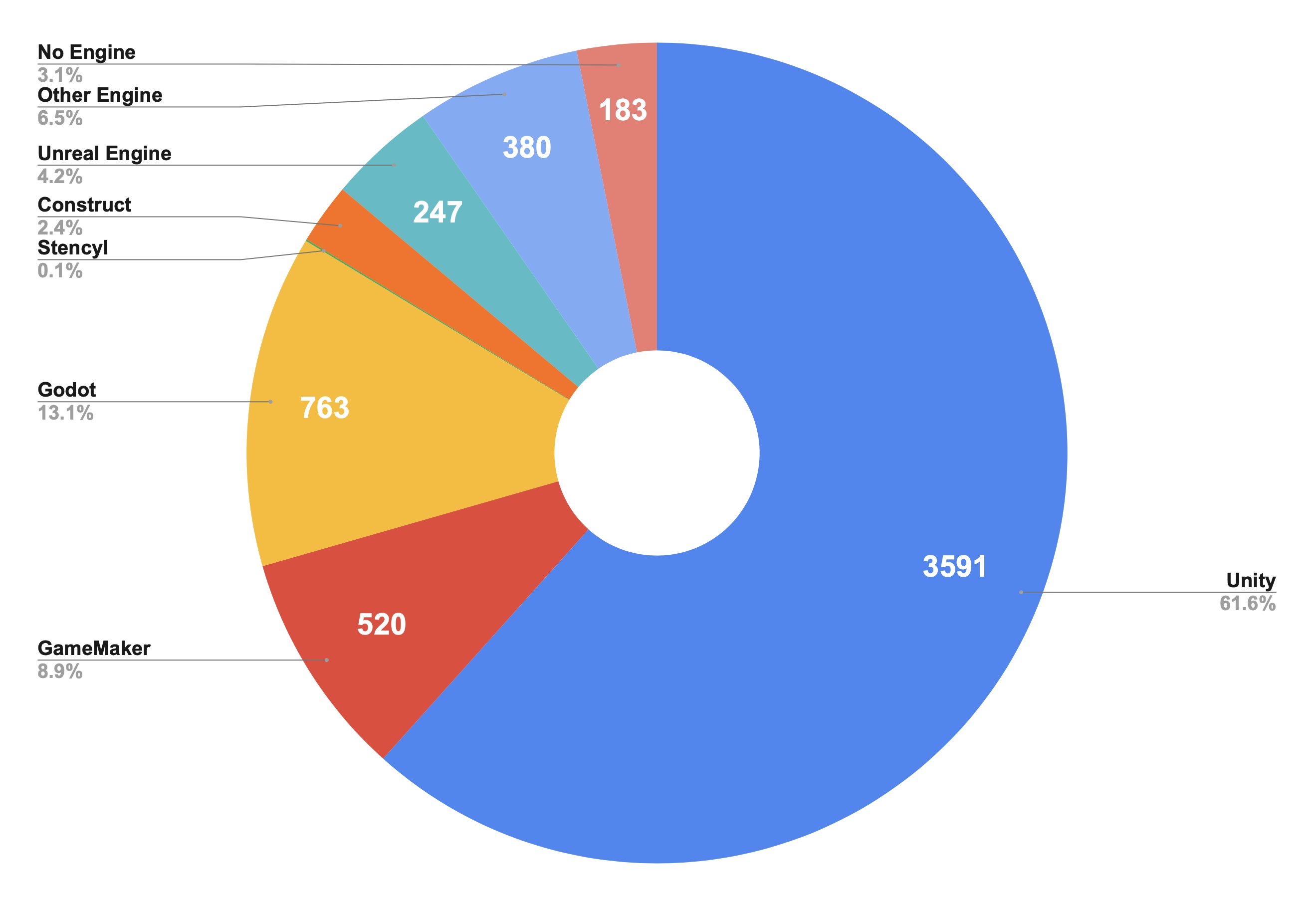

The indie solodev scene has also been taken over by Unity. It’s beginner-friendly and has clear documentation. C# is a popular language and isn’t as intimidating as C++. And it fits everyone’s needs, whether you’re making pixel-based 2D games or beautiful 3D games. Unity is also consistently the most-used engine in game jams:

The engines used in the 2021 Game Maker’s Toolkit game jam.

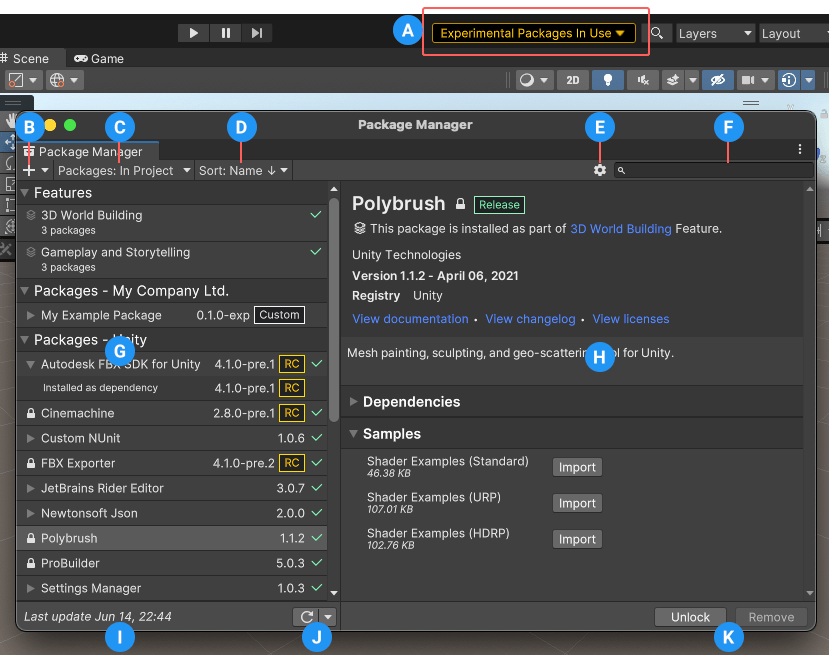

Where is the Unity in Unity?

An old joke rings true—every feature in Unity is either in 0.0.1 Alpha or is deprecated. The rich history of Unity and the wealth of resources hasn’t always been a good thing. There are constantly new features being added, leading to a large and often slow program that includes plenty of features you simply don’t need. The number of unstable features is scary, and there are often many ways of doing the same thing. Every beginner goes through a confusing moment of seeing GUIText is deprecated, then that Text under UnityEngine.UIElements is the new way to do things, then seeing that TextMeshPro is the best way to do things.

And next month the best practices could be completely different. The Unity ecosystem with many different package versions and complex, shiny new features can seem bloated and unfriendly toward older projects. Unity is also closed-source, making it nearly impossible to make even small tweaks to the core engine. If you need to make a small tweak to the universal render pipeline, you might be better off throwing the whole thing out. This all-or-nothing approach favours small indie devs who don’t have to make any tweaks in the first place and massive companies who can pay for premium access to the Unity source code. To put it simply, there isn’t always much Unity in Unity.

I used to be with it, but then they changed what it was.

Unreal Engine

Epic Games’ Unreal Engine is the standard for AAA games. Unreal Engine 5 had its full release just last month, and the features are mind-blowing. Nanite introduces a dynamic mesh system which allows for complex and fast textures. Lumen introduces fully dynamic global illumination, meaning you can see diffuse bounces in real-time. The video below gives a great overview of these features:

The Future of Graphics?

Unreal Engine specializes in hyper-realistic 3D spaces. Beautiful, open-world games such as Ark: Survival Evolved and Sea Of Thieves rely on Unreal Engine to generate highly performant, realistic worlds. But some beautiful 2D games can also be made using Unreal Engine—look at Tetris Effect, a flashy, shader heavy VR Tetris game, or Octopath Traveler, an artistic JRPG.

Unreal Engine also allows access to the source code, giving developers detailed access to the program’s functionality. Unreal has pushed game optimization further than any other engine, and continues to be a performance powerhouse, also driving massive games like Fortnite and Valorant.

A screenshot from the UE5 demo, showing off Nanite and Lumen technology.

So Unreal Engine 5 is big news, but it’s also big. Literally. It’s 15-20 GB on a fresh install, and with extra packages and build platforms it can be 50 GB or above. The UE5 demo alone is 100 GB! And Unreal Engine 5 can be slow, and by “can be” I mean “is always”. Plenty of libraries have to be loaded on boot, and the graphic requirements of the engine are huge. Epic Games writes in their documentation that their typical system has 64 GB of RAM, an RTX 2080 Super, and a machine having 12 to 16 cores. Granted, there are many ways to optimize the engine, and it’s possible to use the engine on much weaker hardware. But the true power of UE5 requires some intensive work.

And of course, you have no need for any of these features if you’re not making a performance-pushing, cutting-edge 3D title. A pixel-based 2D game would be difficult to work on in Unreal Engine, and solodevs will find the UE workflow hard to manage. UE5 is typically better for larger teams, because the workflow benefits greatly from having specific people managing specific sections—materials and shaders and scripts are awkward to jump back and forth between.

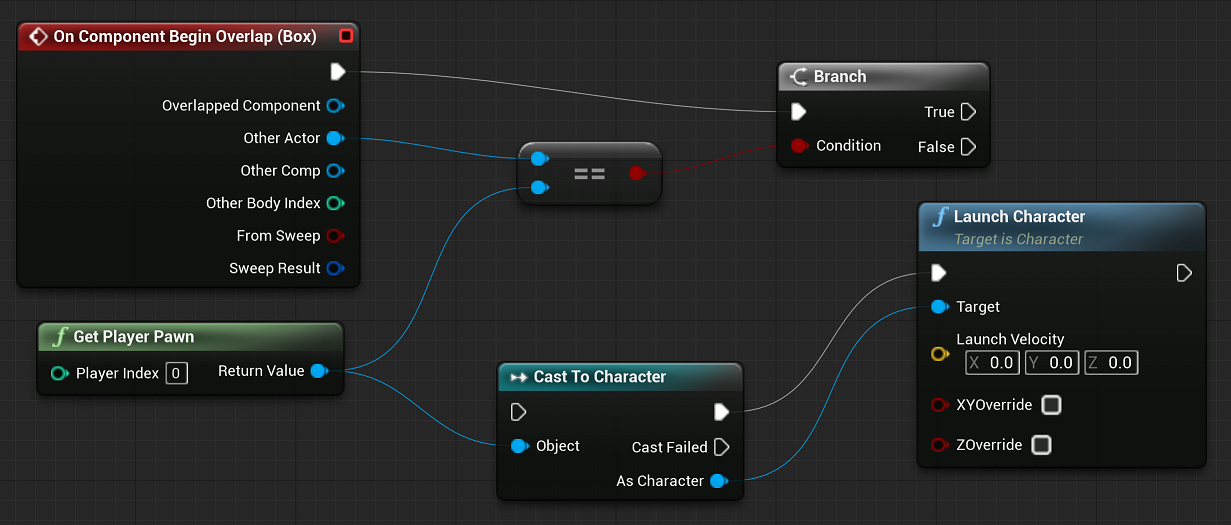

C++ and Blueprints?

The main language used in Unreal Engine 5 is C++. The code is performant and gives you the low-level control you need to write perfectly optimized code. However, C++ is often seen as difficult to write and would be a hassle to write all of the code in. So Unreal Engine includes a convenient visual scripting solution: Blueprints. C++ is preferred for the main system components since it’s highly performant. Blueprints are used by designers to link together systems and create levels and classes. Whereas in Unity everything can be coded in C#, almost all projects in Unreal Engine will make use of both C++ and Blueprints.

Blueprints are a versatile, visual node-based interface.

Much of whether you code in Unity or Unreal Engine will come down to which set of tools you enjoy using more—C#, or C++ and blueprints.

Godot

There’s a new engine on the rise, and it’s a free and open-source jack-of-all-trades engine. It’s Godot, a sleek and beginner-friendly game engine. While there haven’t been any major games developed in Godot, it’s quickly gaining traction. The design of Godot is similar to Unity, but it uses a unique system of nodes and scenes.

Most notably, Godot is small. Unlike the massive and arguably bloated Unity and Unreal, a base install of Godot is only about 40 MB. Things load quickly and startup times are short. The small and modern code base of Godot makes it easy to contribute code.

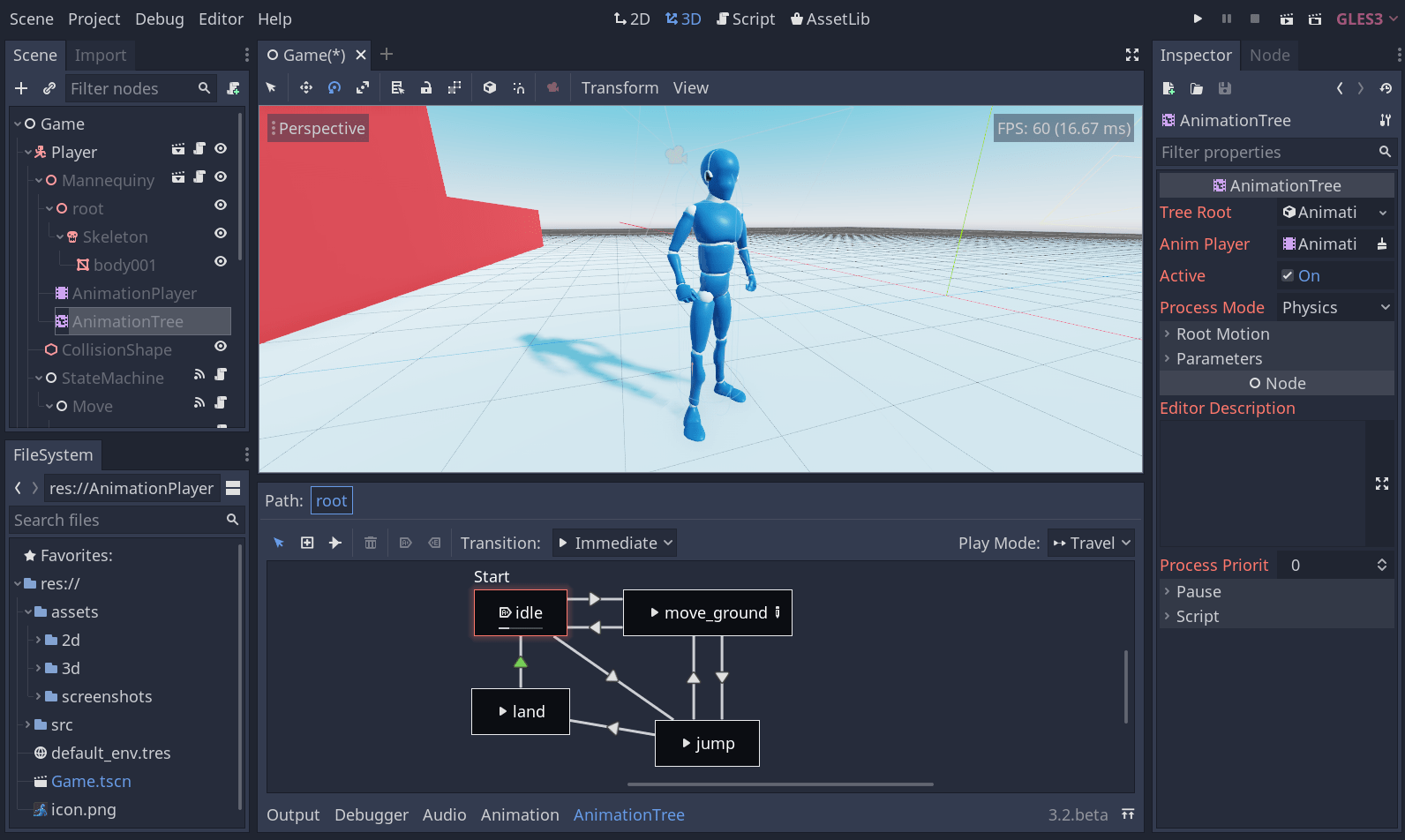

The primary scripting language of Godot is GDScript, which is similar to Python. C# is also a first-class language, with decent C++ support as well, and bindings for Rust and Go. The modular nature of Godot makes customization and extension simple.

The simple-looking Godot has made huge improvements in both 2D and 3D.

Nodes on Nodes?

While Godot doesn’t have AAA titles or stunning graphics to brag about, it does have one of the most elegant systems in game design—nodes. In Godot, a scene is composed of nodes. Scenes have the same functionality of nested prefabs in many other engines like Unity. They can represent many things, from your player character to an entire level. Nodes are the building blocks of your game. They can be nested and combined to produce more complex mechanisms. For example, an enemy might be a scene composed of a sprite node and a collision node. This replaces the idea of prefabs and attributes in an engine like Unity.

The Future of Open Source?

Godot has plenty of open-source tools. Despite having a much smaller community and ecosystem than Unreal and especially Unity, there are still great resources out there. The documentation is high quality and tools are being filled out every day by both full-time developers and volunteers.

Kevin’s Among Us clone in Godot.

Godot isn’t perfect, though. The lack of famous titles doesn’t bode well, and Godot remains obscure. There are less transferable skills to learn with Godot, and the engine is still immature for 3D games. While it lacks the bloat of Unity, it still hasn’t reached feature parity. The upcoming Godot 4 is likely to vastly improve the 3D performance, but like many things with Godot, it lies firmly in the future.

Summary

So to sum it up in: If you’re making a pixel-based 2D game, use Godot if you like coding and GameMaker if you like drag-and-drop. If you’re making a graphically intensive 2D game, use Godot or Unity. If you want to make a 3D game, use Godot if you’re willing to put in the work and use the Godot 4 alpha, Unity if you’re not. If you want to make a beautiful 3D game use Unity or Unreal, depending on which workflow you prefer.

But above all, you have to put in the work—and as much as we want to, we can’t blame the engine for everything!

WCS Club

WCS Club